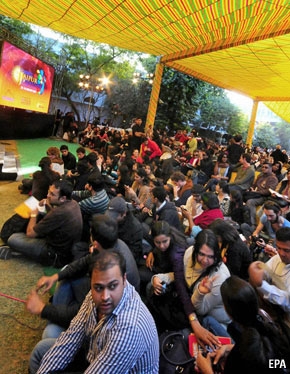

Even a magical realist would struggle with the unlikely tale that unfolded this week at the Jaipur literary festival. Salman Rushdie, an author whom Islamists revile, stayed away, warned by police that two assassins had been dispatched by a Mumbai mafioso to prowl among the literati and murder him.

When it turned out that the police story was more inventive than most novels, Mr Rushdie offered to speak by video link. Yet the plug was pulled on that, amid talk of baying mobs of Muslims. The festival organisers, prodded by the authorities, also sent other writers packing from Jaipur for daring to read out extracts from his book “The Satanic Verses”, banned in India.

Groups that monitor censorship rank India as pretty free. Yet unedifying exceptions exist. In 2010 another writer, Arundhati Roy, was charged with sedition for criticising abuses by the Indian state in Kashmir, disputed with Pakistan. Last year Gujarat banned an unflattering biography of a native son, Mahatma Gandhi. Censors block publications with maps that show the actual line of control in Kashmir, not India’s territorial claim.

Now officials want to impose online restrictions. In October the communication minister, Kapil Sibal, tried ordering Google, Facebook, Microsoft and others to remove web pages critical of political leaders, such as Sonia Gandhi, adding that he worried too about religiously provocative material. He also reportedly told firms to pre-screen all content before it was posted, which he denies.